Mariantonia Gutierrez, an interdisciplinary artist & researcher, talks about the aesthetics of street art and the actual public approval and satisfaction of it in a Wynwood case study.

«I love the art»

Do You Really?

Growing up in Miami, I lived through the growth of Wynwood these past 20 years. It is completely different, and in grand part it was due to art.

Let me elborate.

Wynwood is a neighborhood in Miami, FL that has been getting attention for its increasing development as a mixed use neighboorhood featuring many restaurants, galleries, bars and breweries.

Thought experiment #1

11PM on a Saturday night, y?ou and your friends meet up in front of Coyo Taco, the cars are blasting reggaeton and rap down NW Second Ave, women in tight dresses and heels, men in slacks (because no shorts) with button-down shirts, people walking the streets with a joint while the cop stands in the corner of the street, the artist tagging the sidewalk, every restaurant and bar is packed and charging $20 cover…

Thought Experiment #2

Sunday Afternoon, 2PM, blazing sun on your skin, walking to find somewhere to drink, tourists taking pictures in front of the walls, the line for R house goes around the corner, every restaurant has a wait time…

I have these questions:

Is anyone there just to see art? Does Wynwood really fit the ‘Street Art Oasis’?

Do people actually like Wynwood? Is it just a place to party? How has art transformed Wynwood?

Using my photography, a survey, some urban exploration, and some aesthetic philosophers’ help, I set out to answer at least some of these questions.

Since its inception, Wynwood was an area for working-class families. In the 1920s the area saw a boom in the garment industry and in the late ’80s the district grew in popularity making it the third-largest garment district in the whole country. This attracted the likes of many retailers and we see early gentrification where the value of commercial square footage was rising and many of the Cuban workforces that migrated in the 60s had to move.

In the late 1990s and early 2000’s Wynwood’s scene was revamped. The Bakehouse, which opened as Florida’s largest working artist’s space, was flourishing. The factories and industrial warehouses were turned into studios, bars, restaurants, and creative venues., like Locust Projects and the Rubell Collection. The Rubell’s are actually the family who came up with the notion to use shipping containers to display art on the sand in Miami and the city attracted Art Basel, putting it on the international art-world map.

Many chunks of land were being bought by Goldman Properties, specifically Tony Goldman, who is responsible for the gentrification of SoHo and South Beach. He opened the Wynwood Walls his vision turned to life. Wynwood became known as an arts district. Being filled with galleries, graffiti, and museums, it attracted artists, performers, and creatives from all over the world with its eye-grabbing murals where the entire neighborhood is considered a free outdoor museum.

Wynwood is a hub for visitors interested in eating, drinking, and partying and I fear leaving the art as an added bonus, the way Wynwood fits into ‘street art’ feels distorted.

Sondra Bacharach, an Associate Professor at Victoria University of Wellington for the School of History, Philosophy, Political Science, and International Relations, dives into street art.

In her article Street Art, she describes street art as a new artistic practice that spans all artistic styles.

Explaining street art as wildly diverse in the practices employed, so much so that it refuses to fit into any single category. Bacharach explores how to work that is aconsensual and anonymous can be seen as street art and how this is integral to the art form and to the artists themselves, making the art form a possible defiant and activist capable of changing the world. She specifically mentioned how street artist have opted out of the art world, making art wherever they want, whenever they want, however they want. Aconsensual and ephemeral and diverse are some of the pillars Bacharach establishes as defining of streets art.

In her article, Street Art and Consent she gives examples of street art, highlights the differences between public art and graffiti in comparison to street art, and explores the relationship it has with the public. She explores the literature that distinguishes between the three modes (Street, Public, and Graffiti) and how we classify street art.

Bacharach would describe Wynwood as a partial Street Art Oasis, where art breaks the boundaries and even shows up in the sidewalks and street posts. Wynwood is a statement, where the art is imposed into the city’s environment, where the ‘street artists intervene in the real world, changing it with their works’ (Bacharach, Street Art , p. 458), street art inevitably changes the way we see the streets and street artists actively construct a different world to inhabit in, where the ‘art becomes a dialogue not just between the artist and the public but among members of the public as well (Bacharach, Street Art, 458). However Wynwood is an interesting case because some of the works are privately funded, and painting on some walls could be frowned upon by the artists and curators.

Nicholas Riggle is a philosopher from the University of San Diego who specializes in Aesthetics. In his article, Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces, he explores street art and how it collapses the distinction between art and everyday life by bringing the art world into everyday life. Reading his article, it made me wonder how much street art has affected Wynwood for example. Riggle defines street art as art that uses the street as an immaterial requirement, as an artistic resource, that undoubtedly changes the landscape. He gives it characteristics like ephemeral, often illegal that ultimately challenge museum culture for a purer aesthetic experience. Featuring a privatized outdoor graffiti exhibit, plus a privatized graffiti museum, and many privatized walls, Wynwood doesn’t exactly fit into Riggle nor Bacharach’s definition of street art, sure the street is used as artistic resource but for what purpose?

Again is anyone there to see the art? And if not, what purpose do the murals and graffiti?

Surely not all for art, mainly for money. Wynwood’s murals serve more as a backdrop for the public, and this can be seen in the way they are strategically placed by the restaurants, or by the building owners to attract more customers into their businesses. Even more so, galleries are store style, where kitschy items can be found for tourists and novelty lovers alike. Wynwood while filled with beautiful art, it’s not exactly all street art. Wynwood is a mix of graffiti, mural works and street art, where the murals outweigh the visual landscape, murals meaning commissioned work where the artist is usually known and paid. This privatization of the artist and their work, takes the aconsensuality of street art away and makes Wynwood a more commercial space instead of the creative melting pot. I argue this because since Wynwood has become this sort of ‘mecca’ for artists, yet the process of acquiring a space to paint in Wynwood, acquiring a mural, is not just only difficult but its become bridge a Miami artist ‘needs to cross’ to become ‘legit’, so Wynwood is not exactly public space.

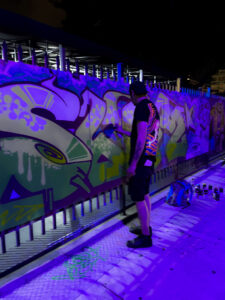

Furthermore on a more personal note, when I have tagged Wynwood, I have to be sure where I tag, because some walls are protected and if I get caught I could get into legal troubles, which is mind boggling because just years ago it was nothing but tags.

How much of Wynwood’s original charm still remain? Murals may embellish the streets and businesses are revamped, the neighborhood has shifted from an arts district to an entertainment district. This changes the demographic of the patrons, the price point, and even the nature of the space.

Overrun with developers, in 2015 Wynwood rezoned to allow the area to have «residential, entertainment, and culinary options,» according to Taylor Cavazos, who is a senior account executive for Kivvit, a public relations firm hired by the Wynwood Business Improvement District, which allows residences up to 12 stories high. Currently there are over 15 residences being built in Wynwood, most of which feature art walls, and murals to further push commercialized street art, and attract the likes of tourists, big-wallets.

Its interesting because Wynwood has become this semi cliché yet still super popular spot, filled with art that is neither good nor bad, and has turned into a mini theme park, fully commercialized. The Wynwood Walls is no longer free! The art is just a sort of background now, which is sad considering the art is the main reason it is in the position it is now.

More interesting however, is how I decided to ask Reddit, specifically in the r/Miami thread which is filled with locals and Miami lovers, their opinions of Wynwood.

Public Opinion

Reading the responses, I was shocked at how many people dislike Wynwood, or think of it as a gentrification zone. It’s a sad reality, but Wynwood’s art is a marketing tactic for developers and big money to make more money of of us. However, it is still such an important place in our community, local artists, like myself, are using Wynwood as a point of connection, where artists can meet and talk about the future. The alternative arts scene in Miami is the underground Wynwood, the side galleries, the small bars, the fly posters on the walls, the tags on the sidewalks, the stickers in the bathroom.

Wynwood definitely has changed, but it’s broadened the definition of street art. Wynwood has allowed street art to encompass more than just graffiti or tags, Wynwood allows street art to be the murals, the bar bathrooms, the sidewalks, and the crossing lamps. Wynwood has created a vibe, a distinct aura, that is a mix of so many things because Wynwood is different on every corner you turn. Wynwood brings the art to everyday life, which theoretically could make us enjoy our spaces more which makes us want to be in them more requiring more restaurants, bars, housing, etc.

It’s going to be interesting how the art scene continues to develop as the city continues to grow.

References

Bacharach, Sondra. “Street Art and Consent.” _The British Journal of Aesthetics_, vol. 55, no. 4, 2015, pp. 481–495., https://doi.org/10.1093/aesthj/ayv030.

Goldblatt, David, et al. «Street Art.»Aesthetics: A Reader in Philosophy of the Arts, Routledge, 2017, pp. 456–458.

McCaughan, Sean. “These Are the Rules of the Big New Wynwood Zoning Code.” Curbed Miami, 24 July 2015, miami.curbed.com/2015/7/24/9937112/wynwood-neighborhood-revitalization-district-approved.“A Brief History of Wynwood.”

Riggle, Nicholas Alden. “Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 68, no. 3, 2010, pp. 243–57. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40793266.

Rodriguez, Rene. “In Miami’s Wynwood District, the Party Has Overtaken the Art.” Miami Herald, 7 Jan. 2013, www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/midtown/article1946043.html.

Wynwood Art Walk Official, 1 Sept. 2013, wynwoodartwalk.com/brief-history-of-wynwood.